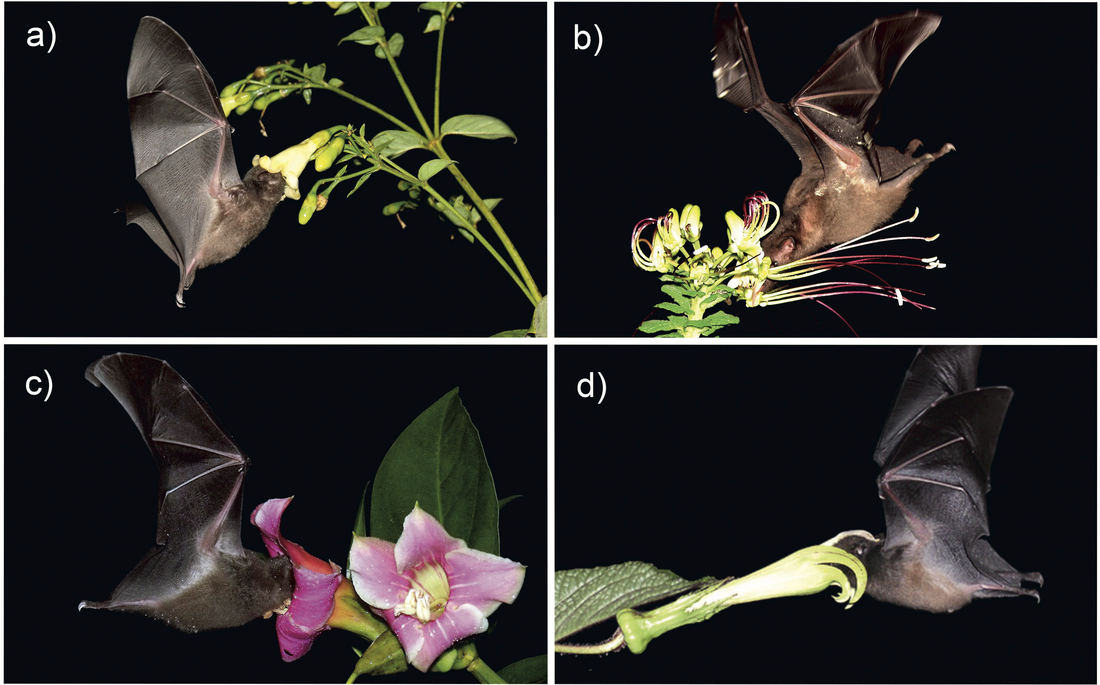

Nathan Muchhala and Marco Tschapka One-quarter (56) of the species of Phyllostomidae have adapted to a primarily nectarivorous diet and serve as pollinators for hundreds of species of flowering plants. Here we review the ecology and evolution of these bats and the flowers that rely on them. A suite of adaptations allows them to feed from flowers efficiently, including elongated rostrums, long, extensible tongues, reduced dentition, well-developed olfaction and spatial memory, and the ability to hover. These adaptations evolved independently in two phyllostomid subfamilies, the Lonchophyllinae and the Glossophaginae, which differ profoundly in their tongue morphology and nectar-feeding behavior: glossophagines have mop-like tongues with papillae covering the distal tip and lap nectar during flower visits, while lonchophyllines have straw-like tongues with papillae-lined grooves along the side and pull nectar through these grooves while keeping the tongue immersed in the nectar. Flowers adapted to bat pollination tend to have dull colors, strong scents, copious pollen and nectar production, and particularly well-exposed flowers. Despite heavy reliance on these flowers, nectar bats will often feed opportunistically on insects and fruit as well, particularly during times of the year when flowers are scarce. However, dietary data are still lacking for many species. More research is also needed to better understand how nectar bats locate flowers, in terms of the degree to which they rely on vision, olfaction, echolocation, and spatial memory in different phases of foraging bouts.

2 Comments

|

Meet the editors!

Theodore H. Fleming, Liliana M. Dávalos, & Marco A. R. Mello Keywords

All

|