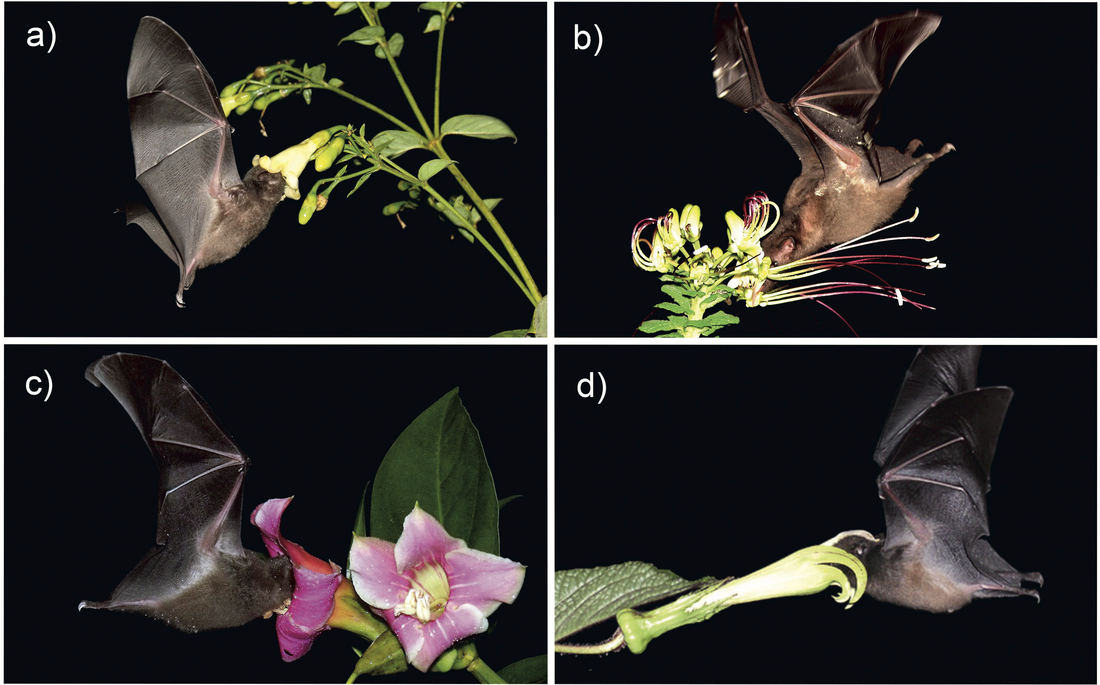

Nathan Muchhala and Marco Tschapka One-quarter (56) of the species of Phyllostomidae have adapted to a primarily nectarivorous diet and serve as pollinators for hundreds of species of flowering plants. Here we review the ecology and evolution of these bats and the flowers that rely on them. A suite of adaptations allows them to feed from flowers efficiently, including elongated rostrums, long, extensible tongues, reduced dentition, well-developed olfaction and spatial memory, and the ability to hover. These adaptations evolved independently in two phyllostomid subfamilies, the Lonchophyllinae and the Glossophaginae, which differ profoundly in their tongue morphology and nectar-feeding behavior: glossophagines have mop-like tongues with papillae covering the distal tip and lap nectar during flower visits, while lonchophyllines have straw-like tongues with papillae-lined grooves along the side and pull nectar through these grooves while keeping the tongue immersed in the nectar. Flowers adapted to bat pollination tend to have dull colors, strong scents, copious pollen and nectar production, and particularly well-exposed flowers. Despite heavy reliance on these flowers, nectar bats will often feed opportunistically on insects and fruit as well, particularly during times of the year when flowers are scarce. However, dietary data are still lacking for many species. More research is also needed to better understand how nectar bats locate flowers, in terms of the degree to which they rely on vision, olfaction, echolocation, and spatial memory in different phases of foraging bouts.

2 Comments

Theodore H. FlemingI review changes in the climate, geology, and biota of the New World tropics and subtropics over the past 30 million years to understand the physical and biological opportunities and constraints phyllostomid bats faced during their adaptive radiation. This radiation occurred during a period of decreasing atmospheric CO2 levels, decreasing global air and sea temperatures, and increasing climatic seasonality that have led to the evolution of a great diversity of vegetation types, including tropical dry forests, montane forests, savannas, and deserts. Reinforcing the effects of temperature changes was the uplift of the major mountains in western North America, Central America, and western South America. Most of the extant diversity of New World noctilionoids is found on the Neotropical mainland in lowland forested habitats, which have existed in one form or another throughout the Americas since the late Cretaceous. A minority of species has evolved in more recent dry or arid habitats, in the mountains, or in the West Indies. Early phyllostomids were gleaning insectivores whose diets differed from those of other families of insectivorous bats. This foraging mode was a key adaptation that led to the radiation of later lineages into several novel (for the New World) dietary niches, including blood-feeding, vertebrate carnivory, nectarivory, and frugivory. Dietary overlap is low between plant-visiting phyllostomids and their avian and mammalian ecological counterparts, reflecting the outcome of coevolution between these bats and their food plants over the past 20 million years.

|

Meet the editors!

Theodore H. Fleming, Liliana M. Dávalos, & Marco A. R. Mello Keywords

All

|